Still seen primarily as a prototyping technology, additive manufacturing is getting a boost from AI and machine learning software that can help with AM decision making.

By Greg Rankin

It’s hard to believe that 3D printing has been with us for more than 40 years. Yet additive manufacturing (AM), which can deliver enormous value, is still greatly underutilized. When properly implemented, the technology can reduce material waste and energy costs, improve part reliability, decrease lead times, reduce or eliminate the need to carry inventory, and optimize the production of legacy parts.

However, transitioning to AM requires not only a change in mindset but more importantly, the ability to quickly and easily identify which parts are best suited for the additive manufacturing process. This is where AI and machine learning are now bridging the gap between traditional AM—where most of its value materializes in the form of functional prototypes—and more advanced additive manufacturing operations.

“We have upwards of a million part numbers,” said Werner Stapela, head of global additive design and manufacturing at Danfoss, an international leader in drives, HVAC, and power management systems. “So, it would be impossible for us to manually analyze each one to determine whether additive manufacturing would either add value or reduce costs.”

Companies, like Danfoss, that are looking to automate the process of identifying which parts should be moved to additive manufacturing are increasingly relying on new industrial 3D printing software that can quickly determine AM feasibility. The platform that Danfoss uses helps manufacturers unlock the benefits of industrial 3D printing by providing a technical and cost-saving analysis.

AM mindset

“We have been utilizing 3D printing for decades, mostly for prototyping, but the Castor3D software allows us to focus on our end components and, more specifically ,the costs associated with that,” added Stapela.

The software’s algorithm and machine learning can scan thousands of parts at once by analyzing CAD files. It evaluates five factors: materials, CAD geometry, costs, lead time, and strength testing, to identify suitable parts for AM. The software can also make design for additive manufacturing (DfAM) suggestions regarding part consolidation and weight reduction opportunities.

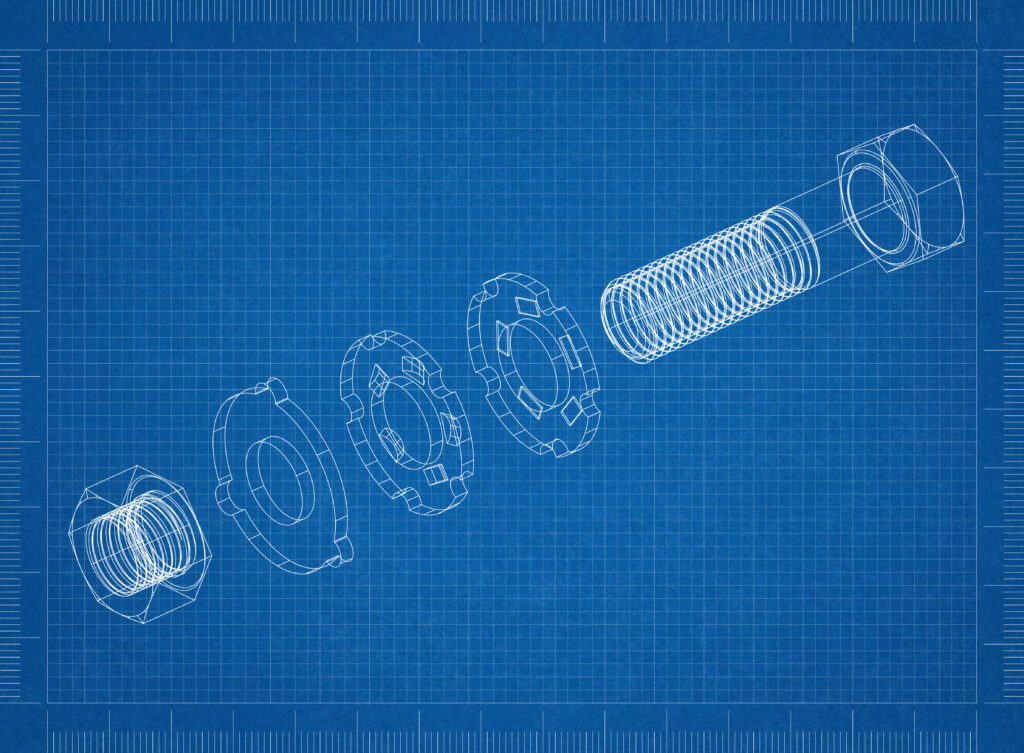

A fastener CAD file. Castor3D software analyzes CAD files, evaluating materials, CAD geometry, costs, lead time, and strength testing, to identify parts suitable for additive manufacturing. (Image courtesy CAD / CAM Services)

“The software delivers a lot of detail. For instance, it will tell you whether your costs [can] be reduced with an improved design or by selecting a different material,” explained Omer Blaier, co-founder of Castor. “So, let’s say a manufacturer determines that a lower-cost material is more important than the strength. The platform would then recommend a material better suited for your design.”

For Danfoss, there has always been a desire to increase its AM processes, both for DfAM on its new products, as well as for its existing product lines and legacy parts.

“There are a lot of big companies out there trying to get engineers to think about additive manufacturing when designing a new component,” Blaier said. “We come at it from the other side, trying to find opportunities within your current designs.”

Connecting the entire process

Few organizations, if any, have a larger library of part designs than the U.S. military, which is increasingly looking to AM as a potential solution to a number of challenges. For example, both the Air Force and Navy are in the process of creating an end-to-end digital manufacturing solution that slashes cycle times from weeks to hours, thus greatly decreasing project costs.

The system will also help to untangle complicated supply chain issues because components could be designed in one part of the world and printed anywhere else on the planet, or even in space, with a push of a button.

The front end of these systems requires the same type of AM decision-making software that automatically identifies suitable parts.

“We are talking about millions, or even billions, of parts in its arsenal. There was just no way the U.S. military could go through each one of those manually and figure out which components could be additively manufactured, which ones should be, and which ones can be improved by moving them into an AM process,” said Scott Shuppert, CEO of CAD / CAM Services.

A Texas-based prime contractor for the U.S. federal government, CAD / CAM Services was brought in to integrate several commercial-off-the-shelf technologies into what the Air force calls the “Factory of the Future.” This integration will enable the Department of Defense and other large manufacturers to manage and scale their AM processes.

Capitalizing on additive manufacturing

“By bringing in the Castor software into our enterprise-wide solution, we are seeing organizations cut their costs by an average of 40-60 percent,” Shuppert added.

As an example, Stanley Engineered Fastening (SEF), which has a diverse portfolio of fastening products serving numerous industries, was looking to lower costs on its production floor, improve part production lead times, and increase manufacturing flexibility.

As part of that, the production line at Stanley’s manufacturing facilities around the world is made up of highly customized parts, with complex geometry, and runs at low annual production volumes. It would take about eight weeks for a new part to be produced and tested. Costs would quickly escalate when the process required multiple iterations.

Wanting to transition some of the processes over to AM, Stanley went looking for a platform that could automate the selection of high-end 3D printing for end-use parts. It was also looking to produce parts using more sophisticated materials like aluminum, titanium, and steel.

“Not only were we able to produce the first Stanley Black & Decker 3D-printed metal production part,” said Moses Pezarkar, a Stanley manufacturing engineer. “We were able to reduce lead times from eight weeks to nine days and decrease our costs by 50 percent.”

The engineering team at Stanley has since ramped up the number of parts the software system is analyzing to further capitalize on additive manufacturing.

Marching forward

With potentially dramatic cost and time savings, business leaders are looking to further expand AM’s footprint in their production process. Aerospace and medical equipment industries are leading the way [in using] AM for end-use parts. In addition, machinery, industrial equipment, oil and gas, and energy are beginning to take advantage of AM beyond prototyping.

Companies are increasingly relying on new industrial 3D printing software that can quickly determine the feasibility of making a part via additive manufacturing. (Image courtesy CAD / CAM Services)

A major shift has also come from an educational standpoint, where universities are increasingly adopting more 3D-printing curricula and buying 3D printers. This promises to deliver more AM-minded design engineers into the workforce. This, along with AM decision-making software systems, promises to speed up the adoption of AM beyond prototyping.

Greg Rankin is a Houston-based freelance journalist with over 20 years of experience covering technology, CAD and industrial design engineering.